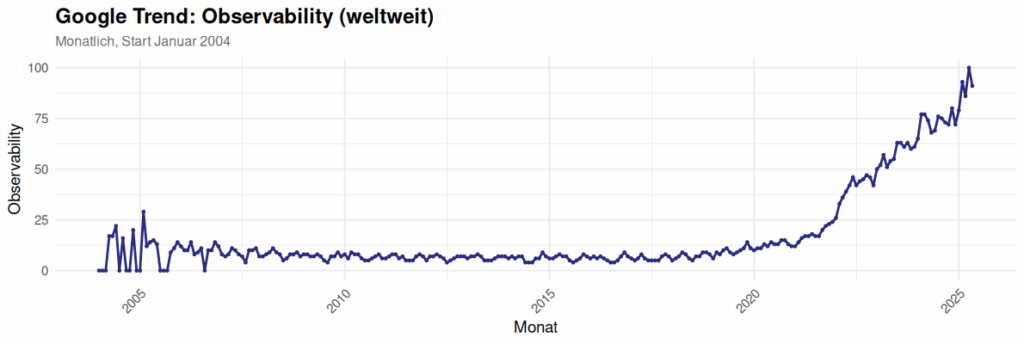

The term observability is on everyone’s lips and is often touted as a modern solution to dusty old, static monitoring. All manufacturers offer it, all users need it, preferably a lot and right now.

However, if you read through product descriptions and blog articles on this topic, you will notice that there is no really uniform definition of the term. What do I mean by that? Depending on what you read, observability is sometimes “an approach to improving observability” or “an element of modern IT infrastructures” or “understanding the status of a system based on its output” or “a process for detecting faults” or “a property of a system”. Of course, terms like to change their meaning depending on the context, but it seems to me that this term is already very overloaded. Even Wikipedia throws its hands up in the air and writes: “The definition of observability varies by vendor”.

As a trained linguist, I can’t just ignore that! Let’s try to define the terms observability and monitoring a little more precisely. Time for some etymology!

Observability

Observability is first and foremost a combination of the English words: “observe”. verb to observe) and “ability” (noun, ability). The result is a noun, because in English most compounds get their meaning from the rightmost word (right-headed, for the linguists in the readership). As in German, by the way, the Danube steamship captain is also a captain and not a Danube.

Observability therefore describes the ability to observe something. Incidentally, the term is not new and was first used in 1959:

Observability is a measure of how well internal states of a system can be inferred from knowledge of its external outputs.

Kalman, Rudolf. “On the general theory of control systems.” IRE Transactions on Automatic Control 4.3 (1959): 110-110.

Interesting here, Kalman describes observability as a “measure”, i.e. a unit of measurement for how well one can deduce the state of a system. Even if the context at that time was not IT systems in today’s sense, a similar meaning can be found in many current texts.

A bit strange, the term has ability in the word, but here it stands for a unit of measurement (measure), unfortunately that’s sometimes the way it is with language and “obsermeasure” doesn’t roll off the tongue so well either. Be that as it may, this meaning is at least tangible and clearly defined. So if observability is a skill and or measure, who possesses that skill or measure? Are we expressing the “degree of observability” of our system, or are we describing our ability as operators to observe the system?

My theory is that it is both. Let me explain: Our system (IT infrastructure or software) has a “degree of observability”, if this is “higher” we as operators of the system also have a higher ability to observe the system. A concrete example:

Let’s imagine we have an application that is currently not writing any logs. If we extend the application with a logging feature, its degree of observability and our ability to observe it increases. Or in short, the application and we have more observability. If we add further features, for example if our application also provides performance metrics, the observability increases again.

OK, so far so good. But what do we do now with all this observability that our system has? For example, we can evaluate the data collected in the event of an error. This can be reactive: So I see the smoke coming out of the data center and look for the cause. But also proactively: I regularly check the temperature before the fire starts.

In my opinion, this is where the term “monitoring” comes into play. So let’s put on our linguistics lab coats again.

Monitoring

Monitoring is either the subordinate of the English verb “to monitor” or its first participle. In our context (IT infrastructure), the term usually appears as “IT monitoring”. We can therefore assume that this is the sub-stand form.

It is about the monitoring of IT systems, or the process of monitoring. Monitoring is also not a new term. A quick search reveals this quote from a 1963 mainframe manual:

In addition […] there are large operational questions which will need to be determined in the areas of reliability, error detection, programming system and hardware maintenance under conditions of nearcontinuous operation, automatic traffic and performance monitoring, and automatic accounting.

The compatible time-sharing system: a programmer’s guide. MIT Press, 1963.

Monitoring initially means everything to do with the monitoring of IT systems. The term is often additionally qualified, as in the quote above “performance monitoring”, i.e. the monitoring of performance. Other examples are “status monitoring”, “service level monitoring” or “end-to-end monitoring”.

What is striking here is that this monitoring is always defined by us – the operators. What is meant by this? We define which status is good or bad, what the service level should be, or what the two ends in the “end to end” are. We also define which data is used for monitoring and which metrics are relevant for performance monitoring, for example.

This is precisely where the interplay between the terms monitoring and observability becomes apparent. Our system needs a certain degree of “observability” so that we can carry out “monitoring” in the first place. As soon as we have data and define monitoring based on it, we do monitoring.

The origin of the observability of the system should not be determined strictly on the basis of specific data. You often read: “Metrics + Logs + Traces = Observability”, but this statement limits the term far too much. Observability should include any type of data that increases the observability of a system.

Practical relevance

OK, enough theory! Let’s take a look at whether my analysis is suitable in practice. Of course, I choose the appropriate examples myself, as a proper scientist would do.

Let’s take the OpenTelemetry project and apply the terms. OpenTelemetry is, among other things, API definitions and SDKs for various programming languages to generate telemetry data. For example, metrics, logs and traces. The smart thing is that we all agree on a standard for how this data is mapped and transferred.

We grab the right SDK and build a feature into our application that produces metrics and logs. This communicates the application in OpenTelemetry format with the OpenTelemetry protocol. So we increase the observability of the system because we now have more data to observe the state.

But data alone does not get us anywhere. So let’s install the Grafana Stack, for example, to save and analyze the data. We log in to the Grafana web interface and create a few smart dashboards. We therefore monitor the status of our application using data that we define as important. We do monitoring.

We can also apply the same to log management software such as Graylog (fun fact: Graylog also supports OpenTelemetry from version 6.2). Let’s imagine that we don’t yet have any insight into our server and network infrastructure logs, so our observability is still low. If we now start to collect the data centrally, we increase observability. In the Graylog web interface, we then create some notifications for alarms (too many incorrect login attempts, for example). We define which data is relevant for monitoring, so we do monitoring.

Works quite well, doesn’t it? Sure, meaning is contextual, but at the same time, different definitions for terms are not helpful in the IT industry. When I say “software”, we all know what I mean. We should have a common vocabulary so that we mean the same thing when we talk. Sentences such as“the definition of <insert term here> varies by vendor” must not be our gold standard.